A Warning about Ticks

New Zealand appears to be lucky in having only one major stock tick – it has a long name, Haemaphysalis longicornis, and can be a tricky opponent when it comes to gaining control. Geographically ticks are found right through the North Island, in Marlborough and Tasman and parts of the West Coast.

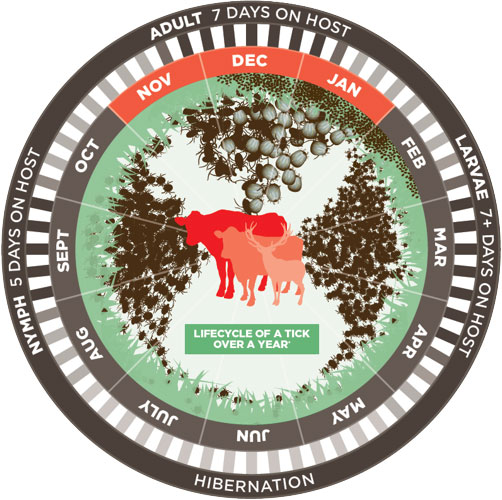

Adult ticks have eight legs and prior to a feed on one of its many hosts (which can include humans), it is about 3mm long, 2mm wide and is red-brown in colour. Once it has partaken of its blood feed it will be 9mm long and 7mm wide and have turned blue-black in colour. Ticks typically have three life stages – adults, which feed on an animal then drop off to lay eggs; these hatch into larvae which crawl onto the animal and feed, then they drop off to moult into nymphs which in turn feed, drop off and moult into adults to start the cycle again.

Over 80% of the tick lifecycle is spent off the animals. This is important as they are often not on the host, meaning that control is not just about dipping animals, it is also about making it harder for ticks to survive off the host.

As you can see in the graphic below, they spend such a short time on the host that an individual tick will have hopped on, fed to near bursting, and dropped off all within a week. So, what you see today is just an idea of what a week’s worth of ticks looks like. There will be many that have fallen off to moult or lay eggs already and there will be just as many likely to hop on next week, during the peak seasons.

The last couple of years with early warm springs have been something of a record for sheer numbers of ticks, particularly around the East Coast and far north; with some veterinary clinics inundated with queries about ticks from mid December until well into February. Ticks were appearing on farms in large numbers and while we usually associate ticks with deer farms, they were causing significant clinical issues on all manner of animals- lots of sheep, some cattle, a few horses and plenty of pet dogs and cats. A key to understanding severity is remembering that heavy burdens on small animals can lead to anaemia and even death; so particularly a concern for fawns, lambs, kids and calves but also production losses occur in adult stock. Of particular note is their role in the transmission of Theileria, which has created all manner of mayhem in dairy and beef herds with serious losses of production and some deaths. In many cases, farmers had never seen ticks on their farms yet their cattle were suffering from theileriosis. This shows that ticks pretty much exist wherever the conditions are right – the right environment means the right temperature and humidity, hence the generally North Island-wide distribution.

Veterinarians can assist clients in both understanding ticks and in providing some clever solutions to tick control. Unfortunately, every tick that you saw in summer and did not kill, will have been able to breed after having a decent feed from whatever host you saw it on. The large ticks are all adults and shortly after they have had their fill of blood they drop off and lay hundreds of eggs. It is the ensuing lifecycle that we are now concerned about and it is likely that we could see a similar explosion of numbers next summer as there are simply so many young ticks about.

Treatments vary with different species but mostly involve pour-ons, dips or washes; the exception is dogs and cats where spot-on and some oral formulations may help with tick control. Depending on which species you are concerned about, a discussion with your vet will help identify the best control options and most efficacious products for your area.

Adult ticks on a red deer. Note that there are smaller ticks behind the back corner of the eye - they have yet to drink much blood so are relatively small and hard to see. Photo: Richard Hilson

Control should be targeted particularly during the nymph season [August to October] and especially at the first onset of adult ticks. In high risk groups like fawns, pre-fawning treatment of hinds three weekly to break the cycle and preparing paddocks with good tree shade and less long grass is useful. You can also consider taking alternate stock like cattle or sheep through paddocks late winter/early spring as this assists with parasite removal and picking up nymphs.

Regarding deer, eagle-eyed vets spot the nymphs in spring (usually mid August to mid September) when TB testing deer and this is a pointer to their control for next summer. This “rise” of ticks seems to occur in a quite defined period and by aiming to reduce numbers then you can reduce adult numbers in summer- and thereby reduce tick numbers for the following year. There is a lot of planning required and we find that once the big ugly adult ticks vanish, the whole tick “problem” seems to fade from memory. Vigilance is important and when the little buggers make another appearance you need to act to avoid a population explosion the following year.

If you would rather not repeat the tick season that was last year, talk to your vet about how to reduce the size of this season's tick burden. Vets and their staff have lots of tricky answers and some novel ideas but would prefer something simple be done in spring than fight more battles in summer.

Thanks to Dr Richard Hilson for his collaboration on this article.